NASA's Intergalactic Mixtape Teaches us how Music can Cure Writer's Block.

What if you shot your spotify playlist into space? What if an alien sent one back?

Two weeks ago, I broke two pairs of headphones, and while waiting for the third one to arrive, I really struggled to write. The sound of the everything around me was too distracting without my carefully curated lo-fi backdrop. But why? I wouldn’t call myself a music nerd; I know nothing about music theory and can barely play the guitar. But if last week taught me anything, it’s that music influences us in some deep, metaphysical way, and NASA agrees.

The Voyager Planetary Mission

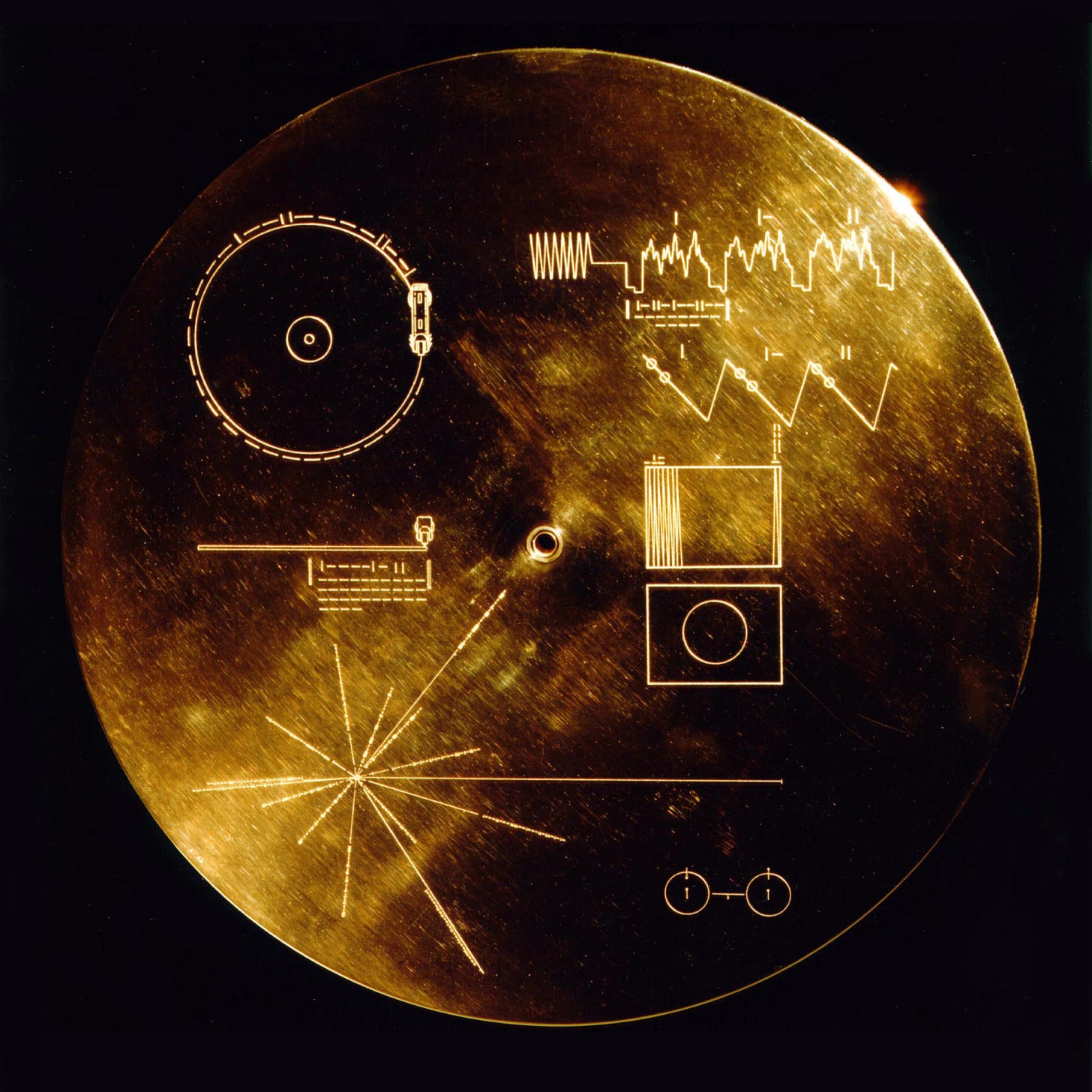

In the 70’s, NASA was getting ready to send out two space probes creatively named Voyagers One and Two, which would conduct studies of the outer planets in our solar system and their respective moons. The plan was to shoot them off into space, where they would spin past Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus and then continue their journey into the void long after we lost contact with them. Carl Sagan, a scientist at NASA, knew this perfectly well, and when tasked with designing some form of plaque for the Voyagers, he pitched the idea of the Voyager Golden Record: a time capsule of all of humanity compressed into two golden discs.

The Voyager Golden Record

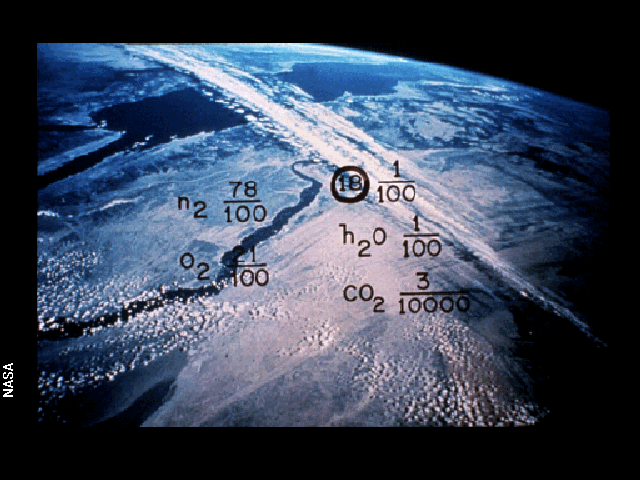

He got the green light and quickly assembled a super-team of scientists, sound engineers and photographers, but they ran into a lot of issues. How do you fit an entire planet into two pieces of metal? Too heavy, and it would mess with the Voyagers’ meticulously calculated trajectories. Too much information and the included needle wouldn’t be able to read the tightly packed grooves. With so much to communicate, how do you decide? The Voyager team settled on universal languages such as visual diagrams, formulas, images, and music.

I have always found the inclusion of music to be interesting. Visuals and diagrams leave less room for interpretation; they present hard facts like our system of mathematics or a diagram of our solar system, but music? We don’t even know if this mysterious alien race could have ears, hearing, or a taste of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons (maybe aliens are more of the Nirvana type). What for us is one of the best classical pieces of music could be a declaration of war to them.

But what the Voyager team knew is what I realised over those two earphone-less weeks: music speaks to the soul. Even if I don’t speak the language of the Mamuna tribe, I can feel the comfort of their song. I don’t know a word of Chinese, but I find its traditional operatic music fascinating. Even if aliens don’t have music they could listen to the tracks on the golden record and experience a snippet of humanity (you can watch and listen to the record here).

The whole project is incredibly fascinating, and it’s also a great love story! If you want to learn more about it, I highly recommend you read The Vynil Frontier by Jonathan Scott. It’s one of my favourite nonfiction novels.

Music and Writer’s Block

The Voyager Golden Record teaches us that music transcends the messy humanity of it all. Maybe one song or playlist resonates when you’re working on a creative project because it speaks to a hidden part of us—the part of us that we share with anything else living and breathing in the deep void of space—the part of us that goes into our art.

If we look at music like that, its power is obvious. It echoes whatever you’re already doing, just like that specific colour palette, that mood board, or that Notion page that you spent five hours formatting. There’s a reason why there are so many channels on YouTube focused on one specific mood or aesthetic.

So, if you’re musically inclined and have writer’s block, don’t write. Look on YouTube for niche little playlists with aesthetic thumbnails and poetic titles. You can also jump onto Spotify (or wherever you get your music) and search for whatever mood your story demands at that moment. Go for a walk, or cook, or play with your children or your dog, or your dolls, whatever you want. The idea is that if the music connects to what you’re working on listening to, it will naturally immerse you in it.

When my new headphones arrived, I felt like my creativity was liberated. Yes, I could listen to music without them, but I couldn’t go to a Café and listen to seaside fantasy folk music while I worked on my siren short story.

It’s not a miraculous drug, but it’s certainly worth a try. Music is a powerful thing. Today, the Voyagers continue their journey through “interstellar space,” and who knows, maybe one day after we’ve all turned into star stuff, some Alien on some planet will be writing about a little race called humanity while listening to Johnny B. Goode.

I’ll cap this off with the message that’s engraved at the end of the record as a sincere thank you to everyone out there who makes all the great music I get to sort into fifteen different Spotify playlists: 1

“To the Makers of Music—All Worlds, All Times”2

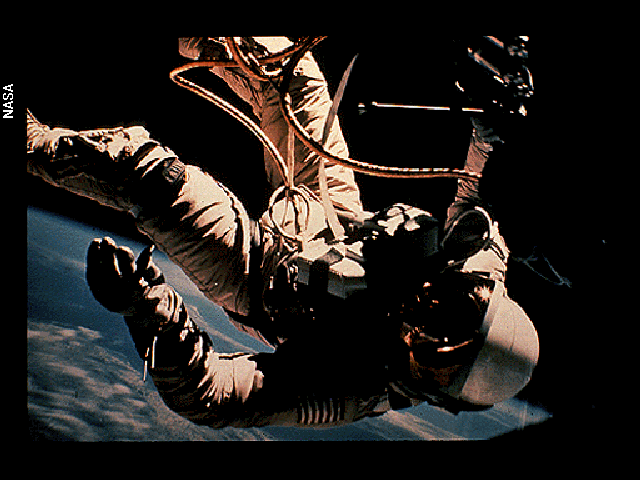

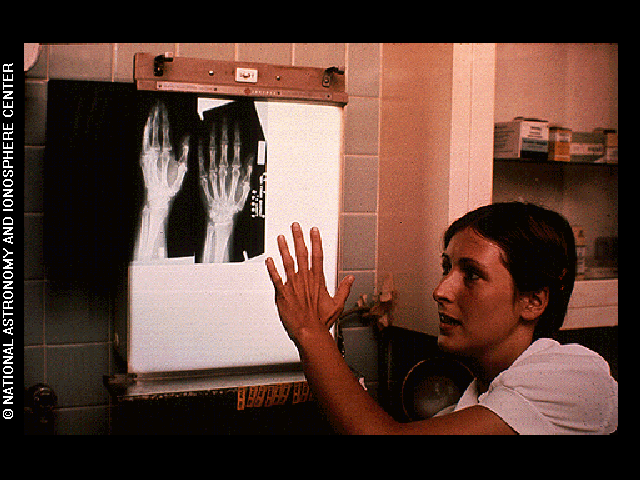

All the images used in this article (except for the one of the record itself) are those included in the actual record; you can check them out here.

You can also read a first-hand account of how the record was created written by Timothy Ferris who worked with Carl Sagan on the project.

Adored! Currently reading Carl Sagan's Pale Blue Dot, and it's absolutely fascinating ^^ I agree with a lot of the points you make, I get a lot of my poetry from music as well [like my latest one ;)] <3